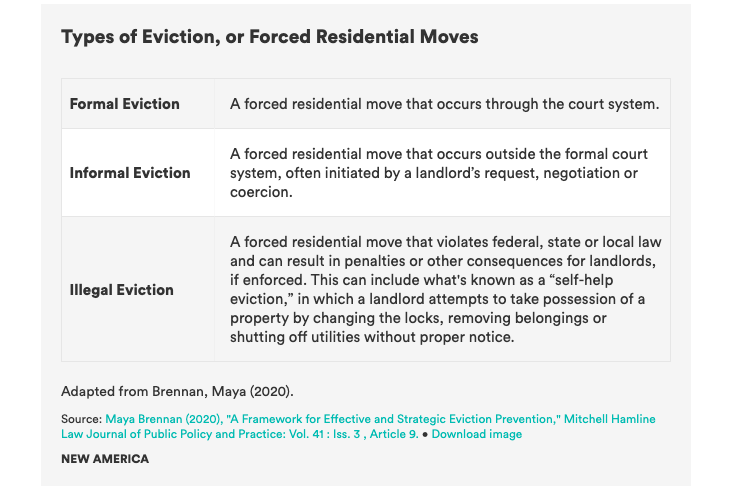

Aside from the formal evictions that go through US state courts, there is another track of informal & illegal evictions. These happen when people are forced from their rentals without the landlord filing a lawsuit, winning a trial, and getting an official court order for eviction.

This report from New America profiles what Informal Evictions are, how they can be measured, what new data sources can be used to track them, and what cities and courts can be doing to measure them.

Informal eviction tactics are built on fear, unequal access to information, and the reality that the law favors landlords’ property rights over a tenant’s right to remain stably housed.

From the New America Report

Informal evictions can be illegal (when a landlord uses lock outs, utility shutoff’s, or other illegal tactics to make someone move). Or they might be in a gray zone, where there is not official harassment or illegal behavior, but there is still coercion for a forced move without a court order.

What are data sources to measure informal eviction?

The report highlights many:

- Household surveys

- User interviews

- Homeless Management Information System (HMIS)

- School district data

- Utilities arrearages

- Postal service data

- Local coalition data

What should cities be doing?

Here are the report’s recommendations (long block quote following):

- Assess the most common methods of informal eviction in your community, and who is most impacted. As discussed above, there are a range of activities that constitute informal eviction, from landlord harassment to shutting off the utilities. Understanding the experiences of tenants, tenant organizers and legal aid organizations in your community will shed light on the varied, and most common, informal eviction tactics that prompt households to move. This in turn will help localities better understand how to define the scope of informal evictions, leading to more informed data collection methods.

- Account for existing tenant protections, housing laws and the legal regimes of tenant-landlord courts in designing data collection efforts. The varied nature of local laws and protections is a major challenge in developing a common definition for informal eviction. Actions that are perfectly legal and commonly deployed in one city or county are illegal in another, blurring the lines about what constitutes an informal versus illegal eviction. To this end, the Legal Services Corporation and Temple University’s Center for Public Health Law Research developed an Eviction Laws Database that provides a comprehensive overview of the entire legal process and other housing laws across the country.

- Develop cross-sector collaborations and assess the range of data sources at your community’s disposal. Understanding the full scope of informal evictions will require a combination of different data sources, and uncovering what data sources exist will require cross-stakeholder representation from various government agencies, county court systems, housing advocates, legal aid organizations, social service organizations, tenant organizers and tenants. During the pandemic, many localities, including Northern Virginia, established eviction prevention task forces, which can help build out datasets over time.

- Understand who is accounted for and who is missing in potential data sources. Unlike the AHS, the CPS ASEC is administered to all household members, increasing the likelihood of capturing data from individuals who are doubling-up, couch surfing or renting a room from another household. Many administrative data sources do not include certain hard-to-reach populations, including individuals who are unhoused or live in congregate shelters. It is critical to understand who is missing in data sources to better understand how to account for these gaps. It could be the case that newly-developed surveys or qualitative studies are needed to address these gaps.

- Pursue data collection efforts that engage individuals who have experienced informal eviction. Informal evictions rest to a large extent on power imbalances between landlords and tenants and a lack of easily accessible information on tenants’ rights and protections. Individuals who have lived through the process possess invaluable insight and can help elucidate the strengths and limitations of various data sources and inform the design of data collection efforts. A recent report on Oregon’s eviction diversion program during the pandemic emphasizes the micro-practices, or “the everyday communications, decisions, and activities through which policy is carried out” in a way that centers tenants’ experience. In addition, Dr. Brittany Lewis lays out an actionable research model that centers tenants in an investigation into eviction in North Minneapolis.