Washington’s third largest city has led the way on housing law reform with a 60-day notice requirement and a powerful new information-sharing system that keeps landlords and tenants in the know.

IN April 2018, all the residents of a 58 unit apartment complex in Tacoma, Washington apartment complex received notices to vacate from their property manager. Half of them were given just 25 days to move out.

Today, providing such a short notice in Tacoma is illegal thanks to the work of ChiQuata Elder, the city’s Landlord-Tenant Coordinator. By bringing together a stakeholder group of tenants, landlords, legal counsel, homelessness services and city code enforcement, she was able to spearhead an effort in which they all rewrote Tacoma’s rental housing code—together.

Implemented with unanimous city council approval in February 2019, the new code instituted a 60-day notice to vacate requirement and a three phase information-sharing system to improve relationships between renters and owners.

“I told landlords, ‘You have the opportunity to work with us on something,’” she recalls, in an interview with the Eviction Learning Lab. “It’s about trust and getting them together; landlords didn’t get everything they wanted and tenants didn’t get everything they wanted but everybody got something we could live with.”

Tacoma’s success story is a blueprint for other cities seeking to keep people housed in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the federal government has made headlines by passing eviction moratoria and providing over $25 billion in rent relief, local governments have far more power in determining the course evictions follow.

By having a Landlord-Tenant Coordinator like Elder, Tacoma was already a step ahead of most other municipalities. She said having a position like hers was crucial to getting stakeholders on board.

“When landlords go to city council and say, ‘This or that is a big problem,’ I could say, ‘I do this every day, we had only two phone calls about that,’” she said. “And at the same time, it was brought up that tenants don’t take notices seriously, which I knew was true— people were getting in touch with my office way too late for me to help them.”

Elder’s group set out to create more time for tenants to relocate when facing a potential eviction. Ashley Duckworth, the city’s rental housing specialist who previously served as a paralegal at Tacoma’s Housing Justice Project and recently joined Tacomaprobono as assistant director, indicated her city’s previous 20-day notices didn’t give people enough warning.

“I certainly couldn’t move homes with 20 days notice,” she said in an interview.

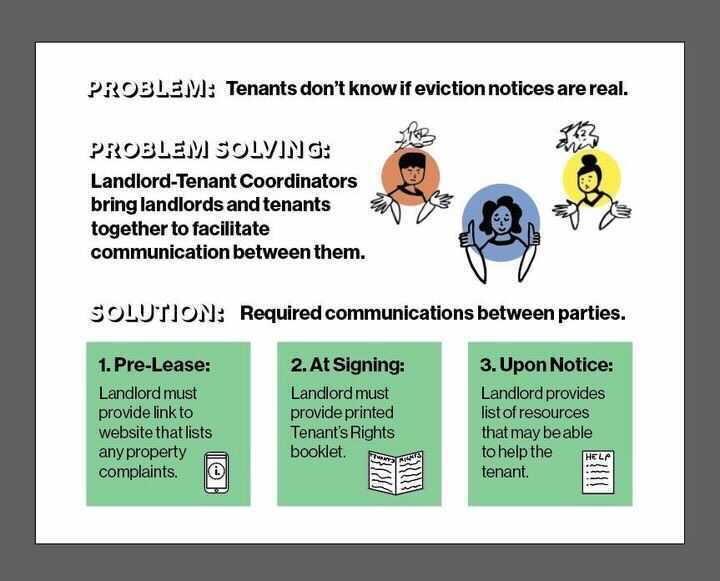

In addition to the extended notice period, Elder’s stakeholder group sought to better inform landlords and renters alike of the city’s housing laws. The idea, a three-phase set of required actions, benefits landlords by improving communication with tenants and allows tenants to learn their rights.

The first requirement directs landlords to educate tenants from the start of their relationship. Before a lease is even signed, landlords have to give tenants a link to a website where they can see if the landlord has code violations or discrimination complaints filed against them.

“We want tenants making decisions that are best for their household,” Elder said, noting upfront disclosure can avert future conflicts. “If there’s a mold issue and you have a respiratory issue, you might not want to rent there; the first phase can help renters make those decisions.”

The second phase occurs if a prospective tenant decides to sign a rental agreement. At that point, the landlord is required to provide a 28-page printed tenants’ rights information packet, available at the city’s website. The packet includes City summaries on the local rental housing code, minimum buildings and structure code, fair housing laws, and the Washington State Residential Landlord-Tenant Act, among other things.

“They have to print it out because lots of people don’t use email regularly,” Elder said. “And they have to re-supply it once a year if the lease goes month to month.”

The third phase occurs if and when a landlord issues any kind of notice that can lead to eviction, including notices to vacate and rent increases. Attached to the notice must be a list of resources for tenants to connect with Elder’s Landlord-Tenant Services office, as well as contacts for free legal advice.

“It saves landlords money, because when tenants don’t take notices seriously, then landlords have to start the eviction process,” Elder noted. “But if the tenants know the notice is a legal one, and they see the resources available, they take it seriously and may not face eviction consequences at all.”

If landlords fail to comply with any of these three requirements, tenants can use it as an affirmative defense to eviction. Elder said her office can also issue a $250 fine per day that a requirement is unfollowed.

“We sent information about the requirements to all the city’s licensed renters,” Elder said. “There’s been a couple landlords we had to call a couple times but we haven’t had to use the enforcement mechanism.”

Because the code was only implemented a year before COVID-19 hit, the city can’t say for sure how many evictions have been averted thanks to the changes: since March 2020, no notices to vacate have been issued due to federal and state moratoria. However, Elder said the city saw a huge decline in eviction filings when the new code took effect.

“It’s really a partnership between landlords, cities, and tenants,” she said. “We all need each other, so the easier we can make it on all sides is going to benefit everyone.”