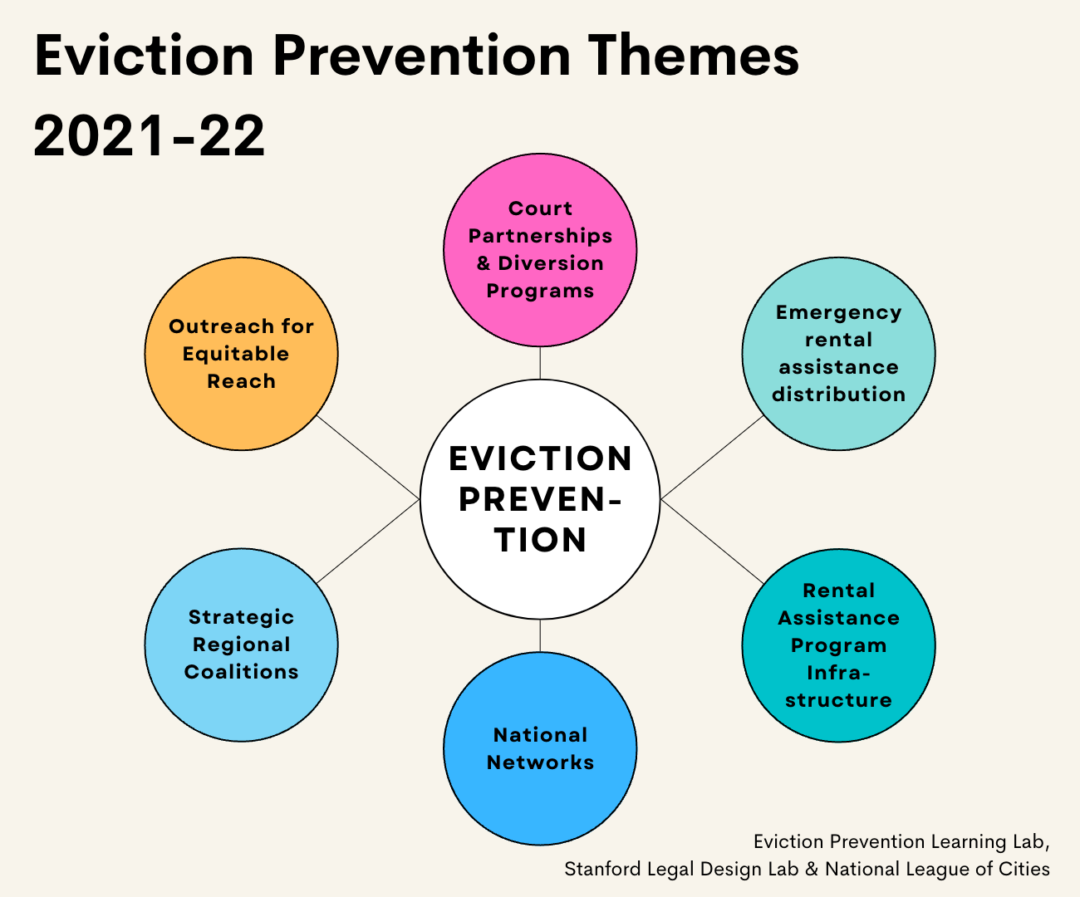

This week at the Eviction Prevention Learning Lab, our quarterly meeting focused on the question “How can city leaders establish strong relationships with court leaders, who can be involved with eviction prevention?”

This focus derives from questions we have heard from local government agencies, nonprofits, and legal aid groups. They’ve been bringing up local issues they’ve run into:

- We want to set up diversion programs, mandatory mediation, or services to help people sued for eviction. But our local courts don’t seem interested in working with us.

- We have heard of other cities that make sure people who are sued for eviction — but who have applied for ERAP— their cases don’t move forward until their ERAP application is decided. But we need courts to partner to make this happen.

- The courts hold a lot of data that we would find useful. The data about which landlords are filing suits, over how much money, for which properties, and with what demographics of tenants — all of this data is useful in short-term services interventions, and long-term strategy planning. How can we build data exchanges?

- We are trying to build a comprehensive regional working group with all players related to evictions and housing in our area. We have tried to include people from the courts, but they haven’t gotten back to us. What can we do to involve them?

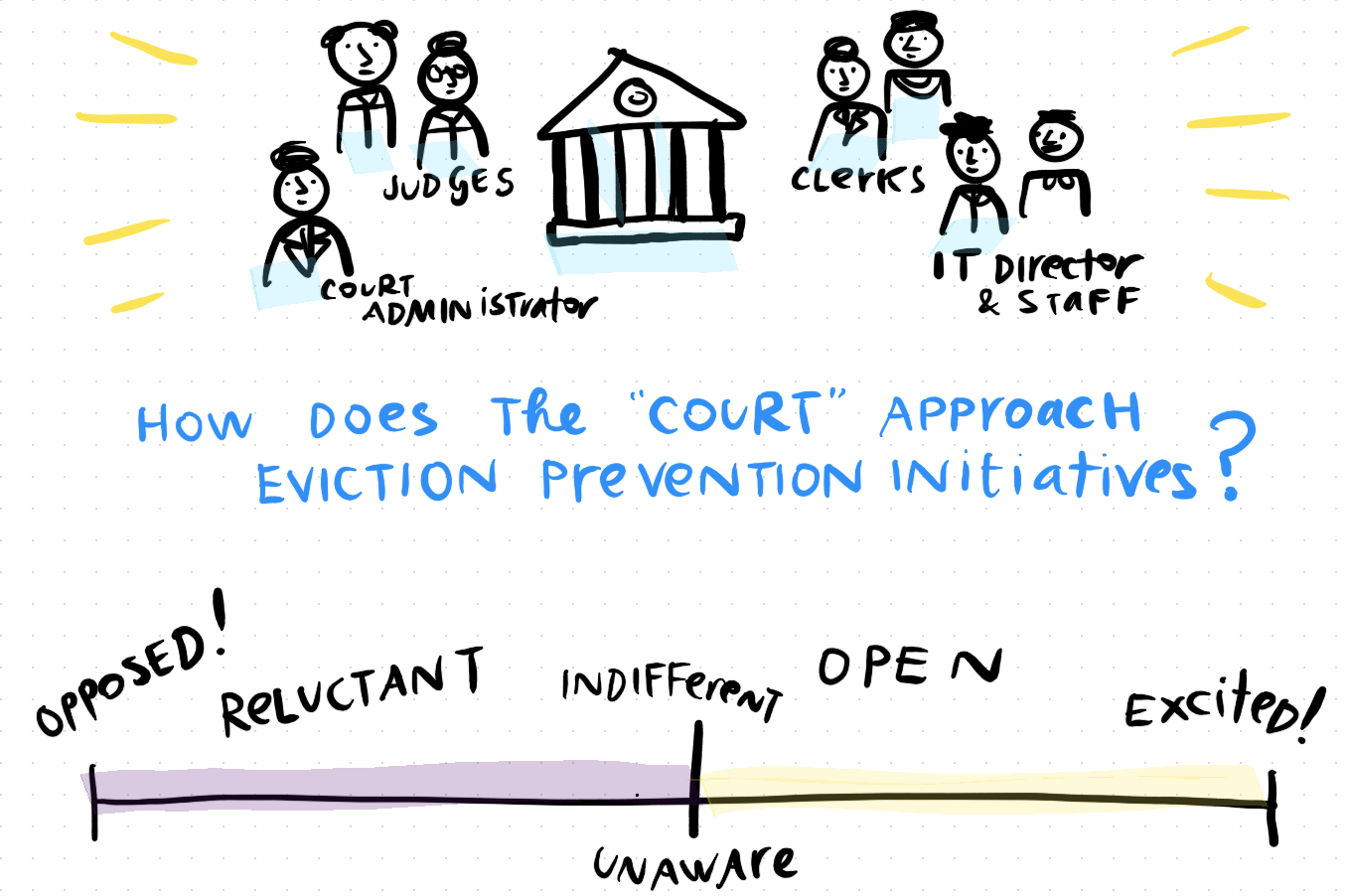

These questions we’ve heard have revealed a trend to us — that city and county agencies are often the leaders of eviction prevention work, and they struggle to build partnerships with the judicial branch (even though all ‘legal’ evictions are going through the courts).

Courts could play a huge role in eviction prevention, and we’ve seen it in many different local regions that have established cutting-edge partnerships. What could courts be doing?

- Early & meaningful outreach to people at risk of eviction. The courts know when a person is seeking to start an eviction lawsuit, or when they do. They know the parties, their contact information, and the nature of the dispute. All of this data means that it could be part of early outreach, as soon as a lawsuit starts (or even when someone is asking for papers to start it), to get the people connected with services.

- Implementing strategies to increase participation. Courts — especially with their authority — can use strategies that encourage more litigants to participate in the eviction process & to be as capable as possible while participating. They can send user-friendly summons and complaints, send text messaging reminders, or even have clerks and judges call litigants who don’t come to the hearing. Once people appear, the court staff and judges can also provide services to ensure litigants can get their forms submitted, evidence presented, and stories across.

- Hosting legal advice and navigation. Courts can either run or welcome legal services that can help a person (for free) to know what their rights are, know how the legal system works, decide on what strategies are best for them, and then fill in documents, gather evidence, and appear at hearings in the wisest way.

- Co-located services & strong direction to use them. If both tenants and landlords are stressed out with the problems they’re having, often they’re not able to seek out resources. The court can be a digital and physical location for them to get other services (financial, mediation, housing search, etc) at the same time and place, where they are already in ‘housing problem-solving mode’.

- Changing the nature of the dispute & possibility to resolve it. The court also has authority to set up how the parties will interact with each other, as they move towards a resolution. Courts can set up procedural guidelines that encourage them to work out a mutually-acceptable solution, like with a judge-run case management conference. They could require use of mediation before a landlord can file a lawsuit, or before a hearing will be held. Or they could change the nature of the courtroom itself, making it more collaborative or problem-solving.

- Data exchanges with related agencies. The court, within the bounds of privacy protections for people at risk of eviction, could establish data agreements with government agencies and researchers. This could allow better tracking of how the formal eviction system is working, who is at risk of eviction, whether interventions are working to decrease evictions, and what dynamics are at play.

Read more about court initiatives on our Eviction Innovation page.

So with all this potential for local courts to play a role in eviction prevention, how can regional leaders get more courts involved?

At our EPLL quarterly learning lab, we heard from leaders in different jurisdictions about what has worked for them. Several models and strategies emerged, that may be useful to other regions thinking about court partnerships in eviction prevention.

We heard some from a strong, organic coalition in Allegheny County and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The agencies and courts there have built an ongoing working group on eviction prevention that has been active for several years, starting before the Pandemic. The Pittsburgh Foundation convened stakeholders from across sectors, and they meet biweekly to discuss problems, identify solutions, and work through the details of initiatives. This has then grown into strong partnerships with courts. The housing agency has staff present in the local magisterial courts where housing cases are heard. They also have a data exchange with the courts, to screen for litigants with active ERAP applications, so these cases can be continued. Rental assistance and mediation services are also co-located and integrated into the court process.

Then we heard from state court leaders in Michigan. There, local eviction diversion pilots spread county-to-county and then were formalized at the state-level during the pandemic. The pilots began with coalitions of government housing agencies and court leaderships coming together, with a focus on preventing homelessness through eviction prevention and especiallly finding ways to improve diversion in the court system. Then judges who had been active in these local pilots spoke with judges in other counties — and moved onto state leadership roles in the capitol. This led to the local best practices then becoming formalized into statewide orders and policies, especially during the emergency policy-making of the pandemic.

Finally, we heard from the Texas Housers in Texas, where the relationships with the court are still in progress. There, the relationships are growing out of a Court Watch program. Teams of volunteers are trained in eviction law and procedure, and they observe virtual & in-person hearings run by local Justices of the Peace. The court watch program has people regularly attending court, filling in structured observation sheets, and then the central group distilling an agenda of what is working and what can be improved. The program is based more on accountability and relationship-building in order to develop more court focus on eviction prevention.

If you are interested in working more on eviction prevention initiatives with courts, our Stanford Legal Design Lab & the NLC have made a toolkit on this topic. Find it here, to see steps and strategies you can use to make progress on court involvement in eviction prevention.